Your business or organisation is planning to have a penetration test – but you’ve never had one before. Let’s run through what a traditional pentest process looks like, and what you might need to prepare for when scoping a web application or website assessment.

If you like our transparent approach to scoping a pentest that’s tailored for your organisation, you can reach out to our team or request a quote.

Getting started

The first step for organisations having a pentest is to decide what type of testing you might need to pursue. As you’re reading this article, you likely have a good idea as to what this is, or perhaps you’ve been asked to arrange a pentest but have no idea where to start.

Purpose of penetration testing

Pentesting has somewhat become synonymous with “security testing” and “security reviews”. You will see many different companies offering services like “Cloud Security Audits” or “Workstation Build Reviews”. But, in reality, this isn’t “Penetration Testing” – and is more in-line with a security review or configuration audit.

The main difference being that penetration testing is an active engagement towards identifying vulnerabilities, and exploiting them, in order to determine if the organisation is vulnerable and what the impact of a successful attack could be (e.g. full network compromise).

Whereas a security or configuration review could involve active testing and exploitation, but is likely just a few vulnerability scans and a manual or automated assessment of how a system or device is setup.

This isn’t to say that these review types of testing aren’t valuable. In a lot of cases they are usually included as add-ons to larger testing engagements – two birds, one stone and all that – but, we’re just setting the scene here. Though it’s technically incorrect, customers have come to see them as part of the “pentest” service umbrella.

Deciding what type of pentesting you need

When the time comes to make a decision for what type of testing you’ll need, in the majority of cases you’ll see the following “types” of testing on annual or semi-annual scopes:

These are the usual culprits for what organisations a) have, b) care about the most, and/or c) are regulated to assess on an annual basis. Ultimately, the business will lead this through risk assessments, internal reviews, and what sort of resources/products they use.

Scoping a pentest

Ok, so let’s say you know that you have a both website for your organisation and a customer-facing web application – and you’re in conversation with a pentest provider. Where do we go from here?

The next step is building a technical scope. This can either be done as part of the discussion with a pentest provider (in our case we welcome chatting through the details either on a call or via email), or you can first decide internally within your organisation before bringing it to a provider.

Just to note before reading on – the information here is more generalised to scoping experiences within the industry and what we’ve observed in our careers. The estimates listed here are for example purposes and may not represent an accurate assessment scope for your applications.

See more about our services and how we operate.

Building a technical scope

At this point you’ll already have a rough idea on what the focus of the assessment would be. The technical scope will be the individual organisational assets that should be targeted (or not targeted – we’ll come to that) as part of testing.

Below are a couple of scenarios with our example scope for a few different types of testing.

Scoping a company website test

Let’s start with the company website. Our example is essentially a “brochure-ware” site that acts as a landing page for the business’ presence on the internet, with limited functionality.

One thing that is useful to know before getting to the scope planning stage is to determine what your organisation sees as a risk for the company website. Some examples of an organisation’s primary concerns for this might be:

- Defacement – the site being compromised in some way that could allow an attacker the ability to modify the content. This could lead to a hit to the business’ reputation.

- Downtime – if the site goes offline there’s a risk to the business from lack of website traffic, loss of sales or marketing leads, which could lead to a loss of revenue.

- Data loss – if the website integrates with any systems, stores customer data (e.g. contact forms), then a data breach brings both a costly impact to the organisation’s reputation and could lead to regulatory fines.

With those jotted down, some of the questions that might be asked by a provider for a website pentest could be:

- What technologies are in use (e.g. a CMS like WordPress, Drupal, etc) or how it was built?

- What functionality does the website offer (form submissions, like a contact or sign-up form)?

- Are there are any integrations with backend services (custom APIs, third-party tracking, etc)?

- Roughly, how many webpages are there?

Let’s make an assumption that our example site is deployed as static-HTML, with no built-in functionality, and only using third-party injected contact forms with analytics tags. What we’re scoping now is a very limited “website pentest”.

The amount of time that is needed to perform this type of security testing will be minimal. There is hardly any functionality that might be at risk of an attack (but again – we don’t fully know that as a provider), and the targeted testing of any integrations that interact directly with third-party APIs would likely be out of scope.

The approach to this type of testing would be more towards a review of the configuration of the web services, and how this could affect the security of the site/user when presented in a browser. This isn’t to say that the weaknesses in the OWASP testing guide are ignored, it’s more that there is no functionality present and so a check to confirm during the enumeration phase is likely sufficient to rule out certain types of testing.

For this assessment, the amount of time allocated might be 1 day of testing. If this were a more dynamic website, say a CMS like WordPress or Drupal, then the time taken might be longer.

One example here might be a very basic website using WordPress, but there are handful of plugins (or even custom plugins) installed. You might want a pentest against the site for assurance purposes, but equally you may want additional time to be spent on research and penetration testing of your custom plugins.

In this case, the time needed for testing may be much higher than the lower-end “brochureware” site described above.

Depending upon whether your cyber security provider charges for the time they spend creating a report, they may have a minimum time of 1 day for this or choose to incorporate it as part of the testing time. Altogether this scope could total 1-2 days for a pentest quote – with reporting included.

With the company website scoped, let’s look at the web application next.

Scoping a web application test

This is where things get a bit more interesting for both the level of detail and the potential for vulnerabilities that might be discovered. For our example let’s say it’s a retail application where customers can shop and make purchases.

As part of an internal review you might identify your organisation’s primary concerns as:

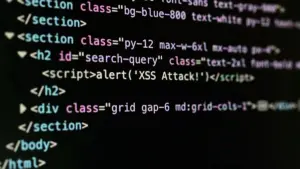

- Data breach – the application being interactive, storing user data, and presumably being a custom platform developed internally increases the potential for vulnerabilities that could either lead to a direct data breach or be used as part of a wider attack (think Cross-Site Scripting or open redirects).

- Availability – if this application is taken offline through some means then this impacts the ability for customers to make purchases, which in turn can cause an impact both financially and to the organisation’s reputation.

- Price manipulation – the organisation may be concerned that there’s a flaw in their payment handling workflows that could lead to the manipulation of prices, promotional codes, or tampering that could cause negative (refund) payments.

These are just a few examples to keep things concise, but are some examples of concerns typically seen as part of scoping discussions for this type of application.

We now know what the main concerns are, but how does that translate to how a penetration test would be scoped?

Well, this highlights the risk impact for the organisation and could direct where the majority of time and effort might be spent to provide security assurances. One example here could be more testing focus being placed upon the payment/purchase workflows than anything else.

Determining application functionality

The next part of the process is for the pentest provider to understand the application a little more. If the URL to the web application was shared ahead of time, then the provider can visit the application and gain some more first-hand information – reducing the amount of time needed during a scoping discussion.

For the sake of brevity let’s just list off some of the questions and topic that might be asked (these aren’t exhaustive):

- Does the application offer authentication/is authenticated testing in-scope? If an application offers user authentication, knowing whether it should be tested or not can change the approach, context, and the time required for testing.

- Does the application have self-registration? If so, this adds additional functionality that would be targeted during the pentest as it is a key method to understanding the authentication workflow from a user perspective.

- How is authentication handled/integrated? This might be phrased differently, but what we’re looking for here is to understand if there is an authentication provider (Cognito, Auth0, Okta, etc) or if the application uses its own custom implementation.

- Are there multiple user roles/permissions, and will these be in-scope for testing? Sometimes, applications will have different user roles (e.g. SaaS platform) and more time may be needed to test authorisation controls across multiple accounts for access control and cross-authorisation testing.

- What functionality does the application offer? More of a generalised question, but it’s to gain an understanding of the scale of the application – i.e. does it provide user profile management, shopping/purchase handling, is there a social interaction capability (where you can see, view, and basically interact with other users or their content), is there user management administration, etc.

- Does the application have a custom API? If the organisation has built their own API backend, it’s useful to know how it was built (REST, SOAP, GraphQL, and/or what language it is written in), how many endpoints there might be, etc.

This isn’t a complete list of questions, but, you might start to see the general theme with the information gathering aspect. The goal of the pentest provider will be to learn as much as they can to build a picture of what they may be testing, and thus how much time they might need to cover the application functionality and the business’ concerns.

So, back to our example:

- We have an e-commerce site that customers can self-register to create an account and make purchases.

- Customers can make guest purchases without registering to the application.

- Whilst logged-in, users can manage their accounts and authentication details, view their order history, payment details, and can create support tickets.

- Users with purchases can create reviews of their product history that others can see.

With all this in mind, the time needed is going to be much greater than that of the company website in order to test all of the available functionality. There are a few different methods that pentest providers may use to break down the level of effort and internally allocate “time” to these.

One option to determining the amount of time needed to include all of the application functionality might be to segment the scope by:

- Allocating a specified amount of time to testing authentication, session handling, and the workflows surrounding the user profile management.

- Setting a time limit for testing the purchase workflow, including the add-to-cart feature, guest purchases, and the overall end-to-end payment process.

- Specifying the time required to test the underlying infrastructure of the application, looking at weaknesses with the web server configuration.

- Explicitly stating the time required for wider business logic testing, looking at issues such as manipulating parameters, and encompassing vulnerability testing such as SQL injection, XSS, and so forth.

- Etc.

From this, the provider would create a quote based on the total time needed, but using the above as an internal reference.

Another option is where providers use a “package” based approach and quote based upon outcome. I.e. the resulting quote would be for a set price and that includes all of the relevant testing of the application without specifically stating a number of days. This can be great for the customer as it means that the pentest will not be cut short if, for example, the 5 days of testing are over and there’s still more functionality that hasn’t been tested.

In either scenario, pentest providers will not typically present a specific breakdown of the individual actions of testing and the time allocation as this could be a very long list – e.g. authentication testing, business logic, etc. You’ll likely receive a quote as a whole, or broken down by the high level testing types, if this includes web app, external network, etc.

Estimating the scope

With that all said and done let’s reflect on what we know about our web application and put an estimate on how long we’ll think this will take:

For the authentication workflows, an example here might be 2 days for full coverage. This of course could change depending upon how the authentication was built and the application functions. If authenticated testing is excluded, there will usually be a discussion around whether attempts at gaining authenticated access is allowed or not.

Then we’ll look at the payment workflows: we could easily spend 2-3 days looking at this (assuming this is custom built and not a no-code solution) as it is a core function of the application, and thus addresses one of the primary concerns highlighted by the business.

Generally, “web server configuration” testing is something that is often done passively. With the great toolsets that are out there, or for providers that use their own internal tooling, there’s minimal need to spend manual effort probing for missing or insecurely configured HTTP headers. However, a good pentest provider will include some additional manually-led testing to look for issues like directory and file exposures, and many more common weaknesses – but this is usually covered with tasks that run in the background.

Finally, let’s bundle the remaining “functionality” together, like the support tickets and review system, and say that it could take about 2-3 days to cover off these. We’re now looking at an assessment that could take 6-8 days all-in.

There’s no hard and fast rules that providers will use to narrow this down, and a lot of what goes in to scope estimation comes from experience. Some providers may create a quote with the upper end of 8 days, whilst some may split it down the middle and say 7 days of testing.

Pentest companies may also charge for their time spent creating their reports – they may add a half a day to the quote to round up any half-days or add 1-2 days on top depending on their internal policies.

Request a free quote

Speak with our security team directly

Experts in providing thorough testing coverage

Professional services you can trust

Fixed pricing with no surprises

Summary – Scoping a Web App Test

Ultimately, what the scoping process boils down to is clear communication on what is a concern for the business, and to understand more about the target assets and their functionality.

If you procure penetration testing for your organisation and it is clear that the test has been over-scoped, under-scoped, or even if it was just-right – then that’s a baseline figure that can be taken forward into future engagements.

To close out everything as more of a quick-reference:

Know what your business concerns are before arranging a scoping call.

This will be crucial for you to be able to provide context during the scoping discussion, and for your pentest provider to understand your requirements to translate them to an appropriate testing scope.

Have a good idea of how your website or web applications are built and their functionality.

Knowing a bit more detail that can be shared with the pentest provider brings a bit of transparency, which can mean a more accurate scope, such as a reduction in overall testing time and costs compared to an off-the-shelf assessment.

Be explicit with anything that is considered out-of-scope.

Reducing the scope of testing can greatly reduce the time commitment and thus the cost of a pentest. This can be achieved in a few different ways, but commonly is done by excluding:

- Functionality (for example, if you know a feature is entirely handled via a third-party, or that any probing of a feature may have a negative impact on the application).

- Whole sections of a website or API endpoint routes.

- Specific types of testing (e.g. brute-forcing credentials, automated vulnerability scanning, etc.).

The downsides of excluding aspects of testing is that there will be a gap in coverage. This will usually be noted in the resulting pentest report so it is clear to both the pentest provider and the recipients of the report.